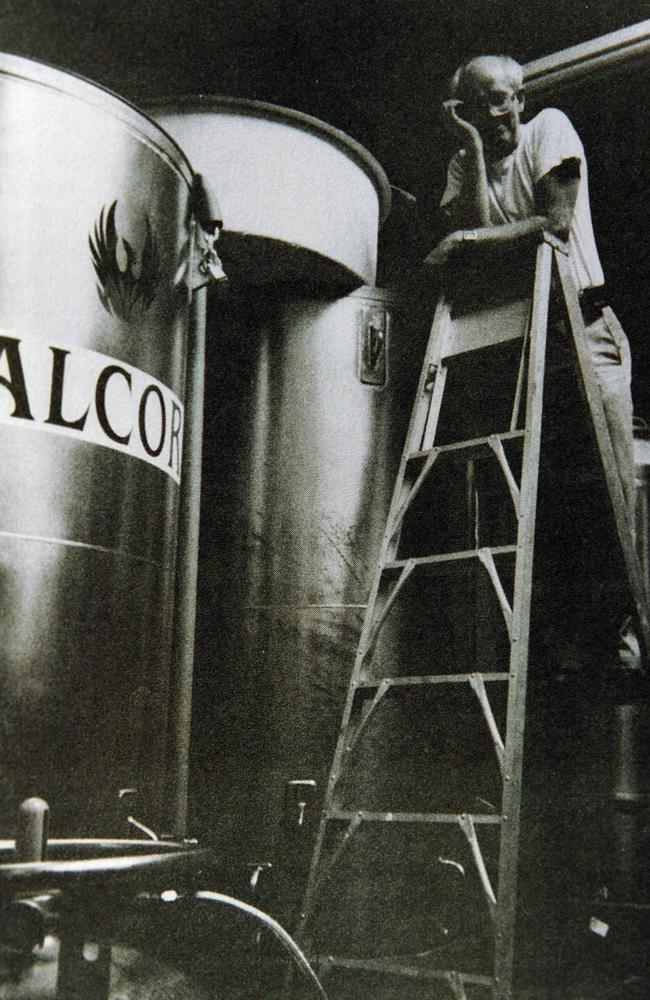

James Bedford’s dewar is stacked vertically along with 145 other frozen people in the Alcor Life Extensions Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona, a luxury suburb of Phoenix on the edge of the Sonoran Desert.

Outside the squat concrete Alcor building, the temperatures can rise to more than 40 degrees for eight months of the year.

Inside, Bedford and the other humans, with enough ongoing financial support to remain frozen indefinitely, are kept at 200 degrees below zero.

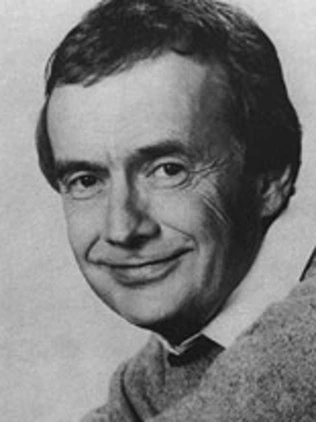

Bedford was a twice married World War 1 veteran and psychology professor who toured Africa and the Amazon in the mid-20th century.

This week, had technology been advanced enough to reanimate him, he would have celebrated 50 years in the deep freeze.

Bedford is the oldest “de-animated”, or cryogenically frozen human being on earth.

Since his original placement in the dewar, hundreds of people have opted to join him in the hope of a second life in the future.

Some are just heads or brains. Others like Bedford are complete bodies.

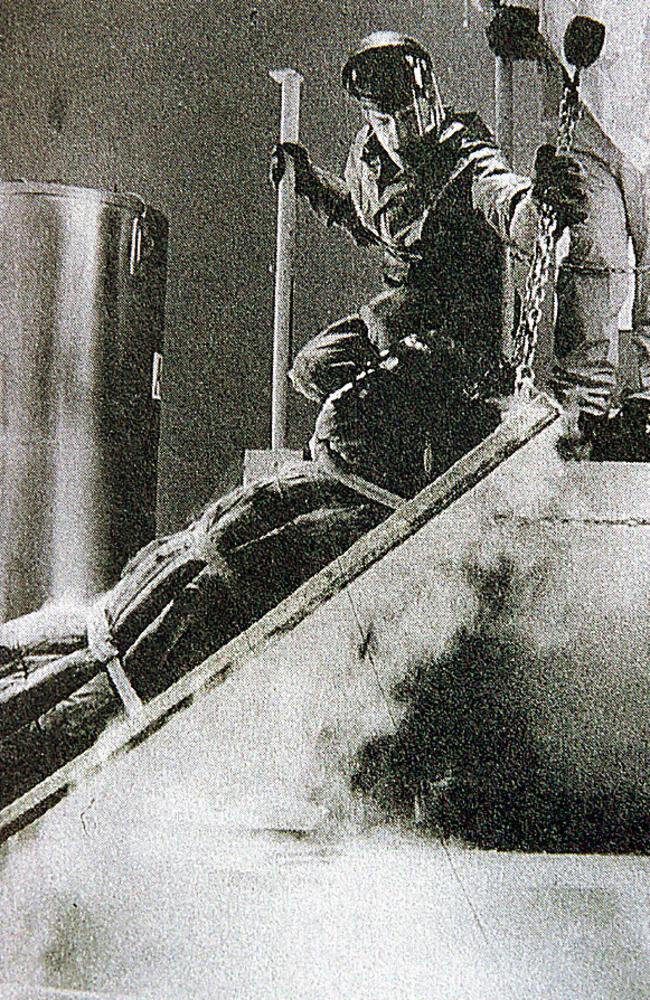

In the last half century, the science of cryogenics, or freezing humans to preserve them for reanimation, has had some spectacular failures when people inadequately frozen have simply started to decompose.

And then there are the bodies which have been hauled around in trucks packed in dry ice as relatives argue over whether to freeze them for the future, or bury them now.

But in the only three cryogenic facilities in the world — Alcor, the Cryonics Institute in Michigan and Russia’s KrioRus — the frozen bodies of the hopeful are stacking up and the technology has vastly improved.

And just last year, a young American scientist gave hope to the future of the science.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology graduate Robert McIntyre for the first time successfully froze and then revived a mammalian brain, that of a New Zealand white rabbit.

When thawed, the rabbit’s brain was found to have all of its synapses, cell membranes, and intracellular structures intact.

The leap to reanimating one of the frozen humans in the three cryogenic facilities may be some time away, but the state of Bedford’s body when he was examined 24 years after his initial preservation was promising.

Bedford was dying from kidney cancer at the age of 73 in 1966 when he made plans to become the first successfully frozen corpse of cryonics pioneer Bob Nelson.

Nelson, a television repairman and president of the Cryonics Society of California, had been inspired by Siberian salamanders which freeze in permafrost for years and walk off when the ice melts.

Bedford provided $US4200 for a steel capsule and enough liquid nitrogen to keep his body frozen at 200 below.

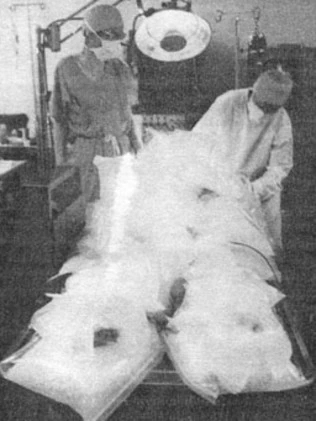

After his death on January 12, 1967, Nelson packed Bedford’s body on ice in a wooden box and loaded it into his Ford utility for temporary storage at a doctor’s house.

When, after a time, the doctor’s wife threatened to call the police, Bedford’s body was placed by his widow Ruby and son Norman with a company as they fought off legal challenges to his preservation.