On one fateful day in 1983, a horrific tragedy now known as the Byford Dolphin incident unfolded.

It has gone down in history as one of the most ‘brutal’ deaths.

The Byford Dolphin, operated in Norway, was a semi-submersible drilling rig.

Saturation divers – professional deep-sea divers – work at depths of 500 feet (152 meters) or more to maintain equipment on offshore oil rigs and undersea pipelines.

Unlike most commercial divers who return to the surface after a few hours, saturation divers can spend up to 28 days on a single job, living in high-pressure chambers between shifts.

It’s lucrative pay but intense and dangerous work.

When working at such extreme depths, divers must ascend and ascend extremely carefully, taking the time to decompress to avoid decompression sickness, commonly known as ‘the bends.’

As a diver descends, the water’s pressure affects every cell in the body, compressing nitrogen gas molecules taken in by the lungs and causing the nitrogen to dissolve into the bloodstream.

Absorbing nitrogen isn’t the issue, the problem is if a diver ascends too quickly. Under pressure, the gas rapidly forms bubbles and expands.

Phillip Newsum, an experienced commercial diver and executive director of the Association of Diving Contractors International, says (per How Stuff Works): “Nitrogen bubbles will form in the bloodstream and those can prevent the circulation of blood, including to the heart.

“That’s when you run the risk of getting decompression sickness.”

Decompression sickness can cause severe joint and muscle pain, delirium, paralysis, heart attacks, and strokes.

It can be treated in a hyperbaric chamber if caught early, where the individual is placed back under pressure, and the pressure is slowly released over hours or days.

But the best prevention is to ascend slowly, allowing the body to ‘off-gas’ the nitrogen naturally.

But commercial divers work at depths far beyond recreational scuba divers, which requires a different decompression method.

A failure in this system led to the Byford Dolphin disaster.

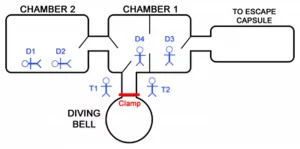

Instead of decompressing like recreational divers – which would take them days to reach the surface – saturation divers use pressurized diving bells and decompression chambers.

For every 100 feet (30 meters) they descend, they must spend approximately one day in the chamber.

To be economical, saturation divers stay at pressure for up to 28 days, commuting in pressurized diving bells.

The last week of any saturation diving job is dedicated to slow and steady decompression before returning to normal atmospheric pressure.

Saturation diving operations require a whole crew.

Life support technicians manage the air mix, the dive control team operates the diving bell, and cooks are there to prepare and serve meals for the divers in living chambers.

Tenders support the divers by managing the ‘umbilical’ – the air supply tubes and communication wires.

On November 5, 1983, an experienced tender named William Crammond performed a routine procedure on the Byford Dolphin.

He had just connected the diving bell to the living chambers and safely deposited two divers in one chamber. The other two divers were already resting in another chamber.

This is when everything went terribly wrong.

The diving bell detached before the chamber doors were closed, causing what’s known as ‘explosive decompression.’

Newsum described it as a ‘death sentence,’ adding: “You won’t survive.”

The air pressure inside the living chambers instantly dropped from nine atmospheres to one atmosphere.

The explosive rush of air killed Crammond and critically injured his colleague, Martin Saunders.

The four saturation divers inside the chamber also met a gruesome fate.

Autopsy reports indicated that Edwin Arthur Coward, Roy P. Lucas, and Bjørn Giæver Bergersen were basically ‘boiled’ from the inside as the nitrogen in their blood erupted into gas bubbles.

Truls Hellevik, standing in front of the partially opened door, was sucked out through a narrow opening, which tore his body apart and ejected his internal organs onto the deck.

“Due to the speed of the incident, it is expected that all the divers passed instantly and painlessly – but the scene left behind was horrific,” notes IFL Science.

The disaster exposed severe safety protocol flaws, prompting significant improvements in commercial diving operations and safety standards worldwide.

It was a wake-up call for the commercial diving industry, which responded by tightening safety measures to prevent such tragedies in the future.

It took decades for the Norwegian government to take responsibility for the Byford Dolphin accident and provide restitution to the victims’ families.

In 2009, an undisclosed sum was given to the victims’ families, including the injured Saunders.

A report into the tragedy suggested it was faulty equipment, not human error, that was to blame for the accident.